Porting a 30 year old game to Go

planted on in: Programming, BASIC, Quick BASIC, Go, Retro and Text Mode.

~6,739 words, about a 34 min read.

Many years ago I found a copy of the Usborne book Computer Space-games, first published in 1982 this book contained a number of space themed games written in #BASIC. One of these, "Space Mines" found on pages 24 and 25 of the book stuck with me and six years ago I ported it to Golang.

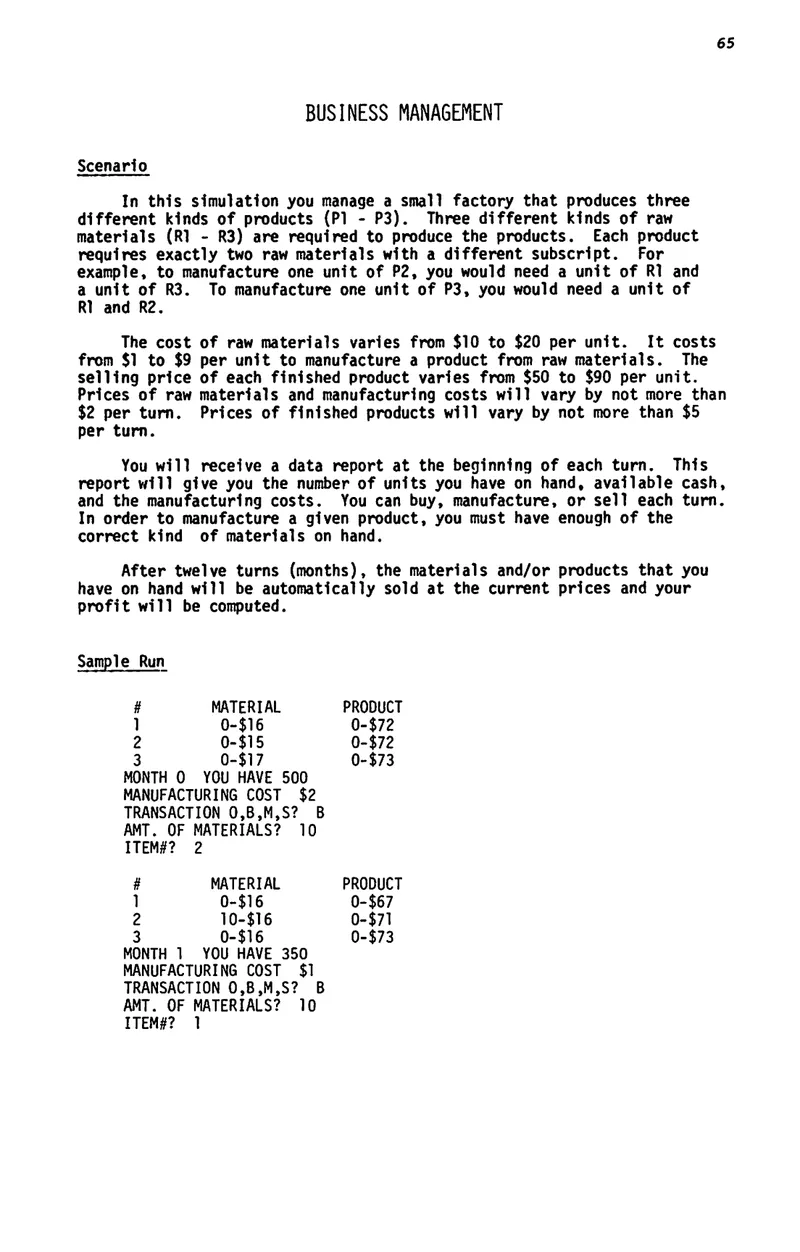

Last year I bought a copy of Stimulating Simulations 2nd Revised edition by Engel, C.W first published in 1979, this book contains a number of simulations written in BASIC alongside block diagrams (flowcharts) that describe their execution order. Of the programs in the book one stood out to me as being similar to Space Mines: "Business Management."

Paraphrasing from the books scenario; in this simulation you manage a small factory that produces three different kinds of products (P1 - P3). There are three different raw materials with each product requiring two materials in order to be manufactured. For example in order to manufacture a unit of P1 you would need one unit each of R2 and R3, to manufacture a unit of P2 you would need one unit each of R1 and R3.

Raw material cost will vary from $10 to $20 per unit while it costs between $1 to $9 per unit to manufacture a product. Similarly, the selling price of each product will vary from $50 to $90 per unit.

The simulation runs for twelve months, after which all stock on hand is sold and your final profit (score) is calculated. Each month you're presented with the current material costs and product price and asked if you want to buy materials, manufacture or sell products. You can only do one of these actions per month.

This game is very similar to Space Mines where you bought and sold mines, bought food and sold ore. I'd like to first port this "Business Management" game to Go and then merge it with Space Mines into a form of Space Colony simulator.

But first, onwards to the port!

—

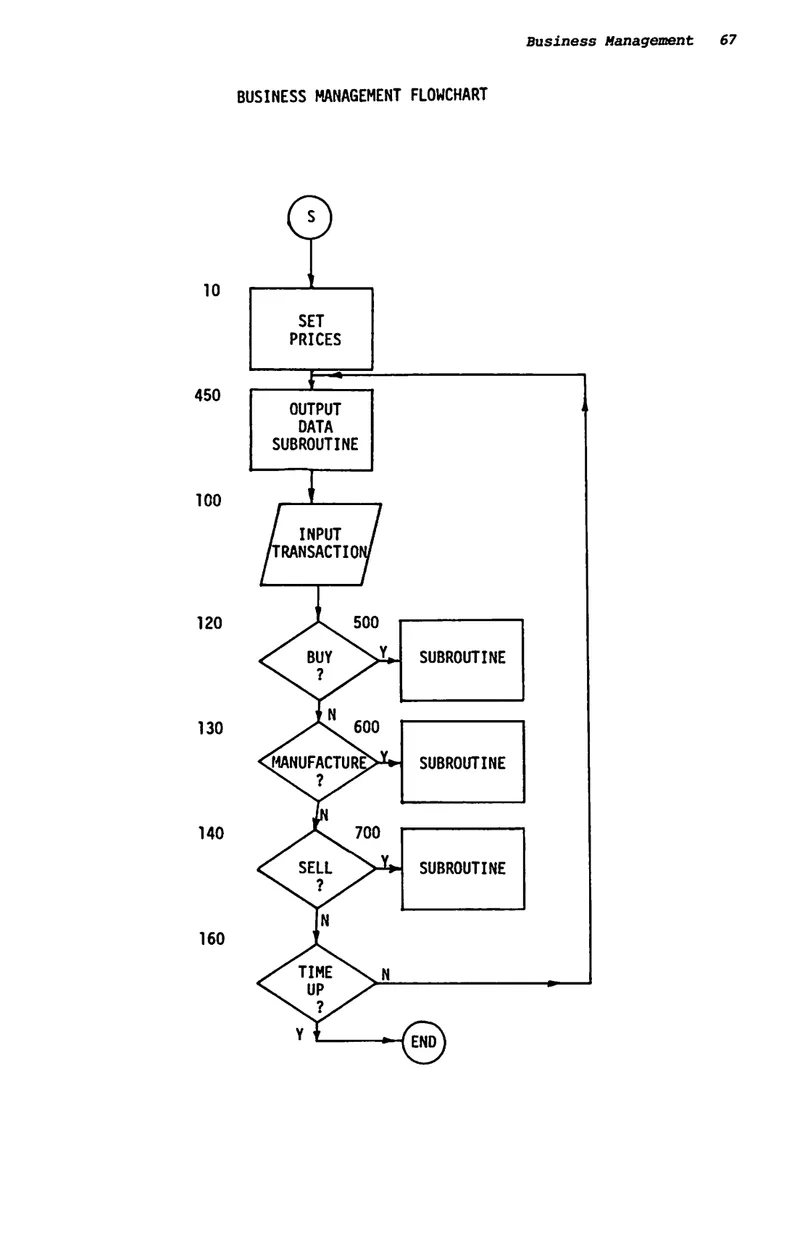

As shown in the flowchart above the game is broken down into distinct functional blocks: Set Prices, Output Data, Input Transaction, Buy, Manufacture, Sell and Time Up (Endgame). All in its 780 lines of BASIC, however it will be distinctly more in Go because we will not be using GOTO and grabbing player input is more complex in Go than a simple INPUT "TRANSACTION O,B,M,S? ":T$.

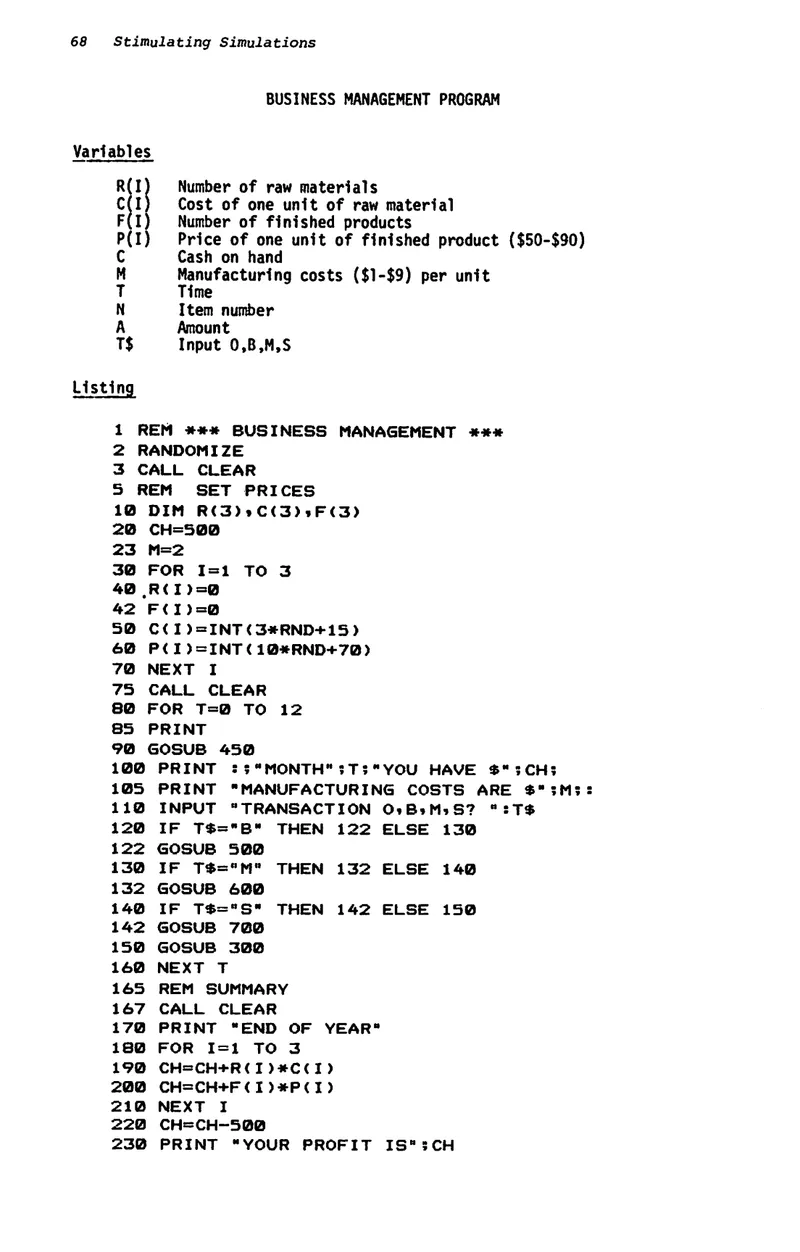

Before the code listing, the book documents the following variables and their usage:

R(I)Number of materials on handC(I)Cost of one unit of raw materialF(I)Number of finished productsP(I)Price of one unit of finished product ($50-$90)CHCash on hand[1]MManufacturing costs ($1-$9)TTimeNItem NumberAAmountT$Input O,B,M,S

The first seven of these pertain to the game state and lend themselves nicely to a Factory struct:

type Factory struct {

resources []int // R(I)

resourceCost []int // C(I)

finishedProducts []int // F(I)

productValue []int // P(I)

cash int // CH

manufacturingCost int // M

month int // T

}The BASIC code begins by defining the initial values for these in its Set Prices section, note any line starting with REM is a comment:

1 REM *** BUSINESS MANAGEMENT ***

2 RANDOMIZE

3 CALL CLEAR

5 REM SET PRICES

10 DIM R(3),C(3),F(3)

20 CH=500

23 M=2

30 FOR I=1 TO 3

40 R(I)=0

42 F(I)=0

50 C(I)=INT(3*RND+15)

60 P(I)=INT(10*RND+70)

70 NEXT I

75 CALL CLEARThis edition of the book is written in TI-BASIC for the TI-99/4A home computer, we begin on line 2 with the RANDOMIZE statement; this seeds the random number generator and is still something we need to do today. Line 3 clears the screen and then on lines 10 through to 70 the game state is initiated giving the player $500 money and an initial manufacturing cost of $2/unit.

Generating random numbers in Go is done via its math/rand package, similarly to the above BASIC code, without seeding (RANDOMIZE) the pseudo random number generator will return the same numbers each execution, which doesn't make for a fun game.

import (

"math/rand"

"time"

)

var rng *rand.Rand

func main() {

source := rand.NewSource(time.Now().UnixNano())

rng = rand.New(source)

state := initFactory()

// ... snipI previously wrote about generating random numbers within a range and so shall be reusing that function here in place of the BASIC INT(3*RND+15) and INT(10*RND+70). Before continuing to the Go code, it is interesting to note how the BASIC code obtains integers within a range.

The TI BASIC command RND yields a decimal from 0 to 1 and the INT command is used to convert a value into an integer it does that through truncation. Therefore INT(10*RND) will give a random number from 0 to 9. Given that multiplication comes before addition in the order of operations it can be assumed that INT(3*RND+15) will produce a random number between 0 and 2 and then add fifteen to it for a random range of 15 - 17[2].

According to the scenario description our resource cost should be between 10 and 20, so why is the program initiating it as 15 - 17? I assume this narrowing of the range is in order to keep consistency between runs.

func rnd(min, max int) int {

return rng.Intn(max-min) + min

}

func initFactory() *Factory {

f := Factory{

month: 1,

cash: 500,

manufacturingCost: 2,

resources: make([]int, 3),

finishedProducts: make([]int, 3),

resourceCost: make([]int, 3),

productValue: make([]int, 3),

}

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

f.resourceCost[i] = rnd(15, 18)

f.productValue[i] = rnd(70, 80)

}

return &f

}

func main() {

source := rand.NewSource(time.Now().UnixNano())

rng = rand.New(source)

state := initFactory()

// snip ...We now have nearly 50 lines of Go code to do what BASIC did in 14, initiate the game state. From here the game enters its "main loop":

80 FOR T=0 TO 12

85 PRINT

90 GOSUB 450

100 PRINT :;"MONTH";T;"YOU HAVE $";CH;

105 PRINT "MANUFACTURING COSTS ARE $";M;:

110 INPUT "TRANSACTION O,B,M,S? " :T$

120 IF T$="B" THEN 122 ELSE 130

122 GOSUB 500

130 IF T$="M" THEN 132 ELSE 140

132 GOSUB 600

140 IF T$="S" THEN 142 ELSE 150

142 GOSUB 700

150 GOSUB 300

160 NEXT TThe game runs for twelve "months" denoted by the "main loop" on line 80. For each month the program runs the subroutine "OUTPUT DATA" at line 450 and upon return prints the current month, the players cash on hand and the current manufacturing costs followed by a prompt asking what they would like to do. I am unsure what O is short for but B,M,S is Buy, Manufacture and Sell.

Before I show the Go ported code, lets first look at what GOSUB 450 runs:

445 REM OUTPUT DATA

450 PRINT "ITEM: MATERIALS: PRODUCT:";:;

460 FOR I=1 TO 3

470 PRINT I;TAB(7);R(I);"$";C(I);TAB(19);F(I);"$";P(I)

480 NEXT I

490 RETURNThis handful of lines produces a table that lists the three material and product types along side their respective purchase/sell prices. In my ported code I have condensed this subroutine and the other status output into one function:

func (f *Factory) display() {

fmt.Println("Item: Materials: Product:")

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

fmt.Printf(

"%d%7d $%d%7d $%d\n",

i+1,

f.resources[i],

f.resourceCost[i],

f.finishedProducts[i],

f.productValue[i],

)

}

fmt.Printf("Month %d, you have $%d\n", f.month, f.cash)

fmt.Printf("Manufacturing costs are $%d/unit\n", f.manufacturingCost)

}Once again more lines of code for the same functionality and in my opinion the format of fmt.Printf is a lot more visually difficult to discern than the equivalent line 470 of BASIC.

Running the code in its current state outputs the following:

Item: Materials: Product:

1 0 $19 0 $68

2 0 $10 0 $76

3 0 $18 0 $82

Month 1, you have $500

Manufacturing costs are $2/unit

I have opted to go with capitalised words rather than all uppercase as with the BASIC version, and also added some punctuation however, the result is functionally the same. We have three materials and three types of product we can manufacture as well as the current buying and selling prices.

Next I focused on the prompt from line 110. I am often impressed by how simple BASIC makes things and obtaining player input is one of those. In BASIC we have a one liner: INPUT "TRANSACTION O,B,M,S? " :T$. This prints the request, awaits input and upon return assigns it to the T$ variable. In Go that requires a fair few more lines of code:

func input(prompt string, validator func(string) bool) string {

reader := bufio.NewReader(os.Stdin)

for {

fmt.Print(prompt)

text, _ := reader.ReadString('\n')

text = strings.Replace(text, "\n", "", -1)

if validator(text) {

return text

}

}

}In fairness to Go however, I am doing a tad more with my input function than the BASIC one liner. This function accepts two arguments, the prompt string and an input validator function, it will then enter an infinite loop that only gets broken out of if the players input is valid, repeating the prompt if not.

This is then used within my main loop like so:

for state.month < 12 {

state.display()

command := input("Transaction (O,B,M,S) ? ", func(s string) bool {

return len(s) == 1 && slices.ContainsFunc(

[]rune{'O', 'B', 'M', 'S'},

func(r rune) bool { return rune(strings.ToUpper(s)[0]) == r },

)

})

switch rune(strings.ToUpper(command)[0]) {

case 'B':

// TODO: Buy Raw Materials Subroutine

break

case 'M':

// TODO: Manufacture Subroutine

break

case 'S':

// TODO: Sell Subroutine

}

// TODO: Change Price Subroutine

state.month++

}The next section to fill is the "Buy Raw Materials" subroutine. Here the player is asked the quantity of materials and which material they want to purchase. The BASIC code below is quite simple in its handling of player input, choosing to return to the main loop on error or if the player has insufficient funds.

495 REM BUY RAW MATERIALS

500 INPUT "AMOUNT OF MATERIALS? ":A

510 INPUT "ITEM #? ":N

520 IF (N<1)+(N>3)THEN 522 ELSE 530

522 PRINT "ERROR"

523 RETURN

530 CH=CH-A*C(N)

540 IF CH<0 THEN 570

550 R(N)=R<N>+A

560 RETURN

570 CH=CH+A*C(N)

580 PRINT "INSUFFICIENT FUNDS"

590 RETURNIn my porting of this subroutine I chose to make use of the validator functionality of my input function to give the player more feedback as well as allowing them to purchase more than one material a turn. I intend to extend this program in the future, therefore I wrote two decorators for my input function to be used in the following functions.

func selectInput(prompt string) int {

command := input(fmt.Sprintf("%s (Q to return) ? ", prompt), func(s string) bool {

return len(s) == 1 && slices.ContainsFunc(

[]rune{'1', '2', '3', 'Q'},

func(r rune) bool { return rune(strings.ToUpper(s)[0]) == r },

)

})

if rune(strings.ToUpper(command)[0]) == 'Q' {

return -1

}

i, _ := strconv.Atoi(command)

return i

}

func numericInput(prompt string) int {

num, _ := strconv.Atoi(input(prompt, func(s string) bool {

return len(s) > 0 && strings.IndexFunc(s, func(r rune) bool {

return r < '0' || r > '9'

}) == -1

}))

return num

}If the player tries to purchase more than they can afford, rather than exiting back to the main loop the game tells them in detail and returns to the buy raw materials loop.

func (f *Factory) purchase() {

for {

id := selectInput("Which material to purchase")

if id < 0 {

return

}

amount := numericInput(fmt.Sprintf("That costs $%d/unit, you have $%d. How many to purchase? ", f.resourceCost[id-1], f.cash))

cost := amount * f.resourceCost[id-1]

if cost > f.cash {

fmt.Printf("Purchasing %d units would cost %d, you have insufficient funds!\n", amount, cost)

continue

}

f.cash -= cost

f.resources[id-1] += amount

}

}My purchase function begins its own loop, the player can exit back to the main game loop by entering Q at the first prompt. This prompt as with the main game loop one is made to be case insensitive, either q or Q will quit back to the main game loop, the other three valid inputs are the numbers 1 to 3 for selecting the material type as listed by the display function.

The validation for this prompt is done so by grabbing the first character of the players string input, converting it to uppercase and then to a rune. The slices.ContainsFunc function can then be used to check if it exists in an allow list of runes.

If valid the input is checked to see if its an exit command before being converted into an integer via the strconv.Atoi function. This is then used by the second prompt for selecting the cost per unit.

Validation for the second prompt uses strings.IndexFunc as a way of checking the input isNumeric. This is done by looping through each character and checking that its rune is 0-9.

Finally the cost is calculated and the player informed if they have insufficient funds, else the cost is deducted from the players cash and their resource incremented by the purchase amount. The purchase loop then starts again, giving the player the option to purchase more, or exit back to the main game loop.

—

We shall next look at what GOSUB 600 looks like, this is the "Manufacture" subroutine:

595 REM MANUFACTURE

600 INPUT "MANUFACTURE AMOUNT? ":A

605 INPUT "ITEM #? " :N

610 IF (N<0)+(N>3)THEN 612 ELSE 620

612 PRINT "ERROR"

613 RETURN

620 CH=CH-A*M

630 IF CH<0 THEN 632 ELSE 640

632 CH=CH+A*M

633 RETURN

640 FOR I=1 TO 3

650 IF I=N THEN 680

660 R(I)=R(I)-A

670 IF R(I)<0 THEN 672 ELSE 680

672 PRINT "MATERIALS GONE"

673 R(I)=R(I)+A

674 CH=CH+A*M

675 RETURN

680 NEXT I

682 F(N)=F(N)+A

684 RETURNSimilarly to the "Buy Raw Materials" subroutine this one asks both which item to manufacture and the quantity exiting on error or if all available materials have been consumed. It also appears to have a bug. When consuming materials, if there is not enough of the second material to manufacture the selected product then the first material will be lost.

func (f *Factory) manufacture() {

for {

id := selectInput("Which material to manufacture")

if id < 0 {

return

}

amount := numericInput(fmt.Sprintf("Manufacturing costs $%d/unit, you have $%d. How many to manufacture? ", f.manufacturingCost, f.cash))

cost := amount * f.manufacturingCost

if cost > f.cash {

fmt.Printf("Manufacturing %d units would cost %d, you have insufficient funds!\n", amount, cost)

continue

}

hasMaterials := true

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

if i == id-1 {

continue

}

if f.resources[i] < amount {

hasMaterials = false

break

}

}

if hasMaterials == false {

fmt.Println("You have insufficient materials to manufacture that much!")

continue

}

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

if i == id-1 {

continue

}

f.resources[i] -= amount

}

f.cash -= cost

f.finishedProducts[id-1] += amount

}

}My ported code begins the same as the previous purchase function, in that it asks how much of which product the player would like to manufacture. It then checks that the player first has enough money to afford the manufacturing cost and then enough materials to complete the order, only when both conditions pass does it subtract the cost and increment the finished products count.

—

Next we come to the final user selected function: GOSUB 700, the "Sell" subroutine:

695 REM SELL

700 INPUT "AMOUNT TO SELL? ":A

702 INPUT "ITEM '#? ":N

710 IF (N<0)+(N>3)THEN 712 ELSE 720

712 PRINT "ERROR"

714 RETURN

720 F(N)=F(N)-A

730 IF F(N)<0 THEN 760

740 CH=CH+A*P(N)

750 RETURN

760 F(N)=F(N)+A

770 PRINT "PROODUCTS GONE"

780 RETURNOnce again the BASIC version is very sparse on player comfort, select an invalid product number or try to sell more than you have on hand you get kicked back to the main game loop. I have instead replicated the comfortable input functionality I used in the previous two functions to produce the following ported code:

func (f *Factory) sell() {

for {

id := selectInput("Which product to sell")

if id < 0 {

return

}

amount := numericInput(fmt.Sprintf("You have %d units, of that product, they sell for $%d/unit. How many to sell? ", f.finishedProducts[id-1], f.productValue[id-1]))

if amount > f.finishedProducts[id-1] {

fmt.Println("You have insufficient products to sell that much!")

continue

}

f.cash += f.productValue[id-1] * amount

f.finishedProducts[id-1] -= amount

}

}All that is left to port now is the "Change Price" subroutine and the end game. We shall start with the former of the two:

295 REM CHANGE PRICE SUBROUTINE

300 FOR I=1 TO 3

310 J=INT(5*RND-2)

320 J=C(I)+J

330 IF (J<10)+(J>20)THEN 310

340 C(I)=J

350 J=INT(11*RND-5)

360 J=P(I)+J

370 IF (J<50)+(J>90)THEN 350

380 P(I)=J

390 NEXT I

400 J=INT(5*RND-2)

410 J=M+J

420 IF (J<1)+(J>9)THEN 400

430 M=J

440 RETURNThis subroutine is inconspicuously complex, which becomes apparent in my port to Golang. For each of the three products and materials it modifies their value but only within their range and uses the GOTO equivalent of a while loop to do so.

func (f *Factory) update() {

j := 0

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

for j < 10 || j > 20 {

j = f.resourceCost[i] + rnd(-2, 2)

}

f.resourceCost[i] = j

j = 0

for j < 50 || j > 90 {

j = f.productValue[i] + rnd(-5, 5)

}

f.productValue[i] = j

}

j = 0

for j < 1 || j > 9 {

j = f.manufacturingCost + rnd(-2, 2)

}

f.manufacturingCost = j

}The above port is more or less direct from BASIC to Go and shows the multiple loops used to drift each of the values within their defined range. Both manufacturing cost and resource cost may drift by +/- 2 while a products value may shift by up to +/- 5.

With that done we now have a fully functional game, the only thing left is the end game state. In the BASIC version the game loops for twelve turns (months) before calculating the players overall profit:

165 REM SUMMARY

167 CALL CLEAR

170 PRINT "END OF YEAR"

180 FOR I=1 TO 3

190 CH=CH+R(I)*C(I)

200 CH=CH+F(I)*P(I)

210 NEXT I

220 CH=CH-500

230 PRINT "YOUR PROFIT IS";CH

240 INPUT "PLAY AGAIN? ":Y$

250 IF Y$="Y" THEN 20

260 ENDOnce the players profit is displayed the player is asked if they would like to play again and if so the game state is reset and the main loop resumes. I have ported this to the following netWorth function.

func (f *Factory) netWorth() int {

netWorth := f.cash

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

netWorth += f.productValue[i] * f.finishedProducts[i]

netWorth += f.resourceCost[i] * f.resources[i]

}

return netWorth

}In doing so I now have the entire 109 LoC BASIC program ported and running in 254 lines of Go. Of course in my version I have provided some player comfort through input validation which added to the line count, but also doing certain things in Go simply requires more lines of code than BASIC.

Item: Materials: Product:

1 0 $13 0 $70

2 40 $11 0 $56

3 40 $12 0 $55

Month 11, you have $1530

Manufacturing costs are $1/unit

Transaction (O,B,M,S) ? m

Which material to manufacture (Q to return) ? 1

Manufacturing costs $1/unit, you have $1530. How many to manufacture? 40

Which material to manufacture (Q to return) ? q

Your net worth is $4370

From here the book makes some suggestions for both minor and major changes to the game. The minor changes are just that, minor, such as adding more materials and products and changing the range of values the various buy and sell values can be.

The major changes are far more interesting:

- Increase number of raw materials and finished products.

- Have a storage fee.

- When you buy, prices Increase.

- When you sell, prices decrease.

- Borrow money with interest.

- Add random events, such as strikes, shortage of materials, fires, no demand.

- Provide names for raw materials and products.

While writing this port I came up with a few more:

- Allow the player to buy, manufacture, sell or end turn rather than only one of each per turn.

- Having done the above, purchased materials can only be used next turn, similarly manufactured products can only be sold next turn

- Add a lead time to product purchase, some products might take two or more turns to arrive

- Add concept of limited storage space and purchasable upgrades that unlock more storage

- Add concept of tiered products, with later tiers requiring one or more of the previous tiers product to manufacture

- Add concept of manufacturing queue, being able to add multiple orders to the queue and the ability to upgrade to having more "queue workers" such as buying more equipment

I'd also like to make the game more graphically beautiful while keeping within the #TextMode aesthetic. Finally and this was ultimately the goal, I'd like to merge this game with Space Mines so that the player manages mining resources and manufacturing them for a galactic marketplace and all the challenges that brings.

You can view all the code from this port over at the Go Business Management repository on GitHub

In good old type-in fashion there is an error in the printing stating that

Cis the variable for cash on hand however that is incorrect. ↩︎My brain still can't look at

INT(5*RND-2)and know its a random number in the range of -2 to +2 or even thatINT(11*RND-5)is a random number in the range of -5 to +5. ↩︎